The Provenance of Thomas Cole’s “View of Florence”: An Unsolved Mystery

Image in the public domain of “View of Florence” (1837) by Thomas Cole, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

During my tenure as the provenance researcher at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), I worked on the provenances of several paintings that had particularly complex and/or elusive ownership histories. I researched these provenances continuously over the course of nearly 3.5 years, following promising leads, hitting dead ends, and hoping to solve the mysteries of their pasts. While I was unable to fill all the gaps in these paintings’ provenances, I did uncover some fascinating elements of their histories.

One of these particularly knotty provenances belonged to Thomas Cole’s Hudson River School 1837 masterpiece, View of Florence. Researching this provenance, with its many twists and turns, was definitely a labor of love, and I half-jokingly told my colleagues it was my life’s mission to close the nearly 100-year gap in its ownership history.

When I began to work on it, the painting’s provenance was as follows:

1838-1839: Possibly Mr. Hunt, Boston

Jonathan Mason, Cole’s friend and agent, wrote to the artist on March 20, 1838, saying he sold the painting to a “Mr. Hunt” on behalf of Cole. Further details about Hunt’s identity are unknown.

By 1839: Jonathan Mason, Boston

Jonathan Mason is listed as the painting’s owner in an 1839 exhibition at the Boston Athenaeum (exhibition catalogues and other records of exhibitions are a great way to trace provenance, as often the lender of the object to an exhibition is documented).

By 1848 – before 1854: Edward James, New York, NY, probably to Henry James, Sr.

An 1848 exhibition of works by Cole held at the American Art Union lists Edward James as the lender of the painting. Edward James, the uncle of novelist Henry James, is among the lesser-known members of the prominent James family.

By 1854-?: Henry James, Sr. [1811-1882], New York, NY

Henry James, Sr., father of novelist Henry James, owned the painting by 1854, when he was listed as its owner in a New York Gallery of Fine Arts exhibition on May 1st of that year. We have some additional – and interesting – documentation for this painting’s having been with the James family: in his memoir of 1913, A Small Boy and Others, novelist Henry James recalls the painting, which “covered half a side of our front parlor” of the family’s brownstone on West 14th Street in Manhattan. He writes that, as of 1913, the painting was “long ago lost to our sight,” which suggests that the painting had not been with the family for quite some time at that point. And indeed, it seemed that all traces of the painting were lost until art dealer Victor Spark acquired it and sold it to the CMA in 1961.

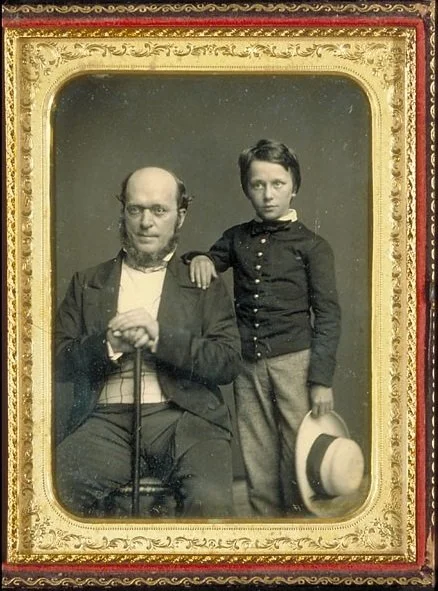

Henry James, Sr. and Henry James, Jr. 1854 Daguerreotype, Mathew Brady

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The first issue that needed to be tackled was the inclusion of Thomas Parkman Cushing in the provenance in between Edward James and Henry James, Sr. How and why did the painting belong to a member of the James family, then pass to someone else, and later return to a member of the James family?

Cushing lent a painting titled View on the Arno, near Florence to an exhibition at the Boston Athenaeum in 1850. However, my research revealed that art historian Diane Strazdes had likely confused the Cleveland picture with a different Cole painting when entering it into the 1983 exhibition catalogue A Lost World: Masterpieces of American Painting 1760-1910, assigning the Cushing provenance to the wrong painting.

The second – and more significant – problem at hand was the massive century-long gap, spanning from 1854 until 1961, in the painting’s provenance, and I worked to close this gap from both ends: Under what circumstances did it leave James’ possession, and when did Victor Spark acquire it and from whom?

Victor Spark, a New York dealer specializing in Old Master paintings and 19th/early 20th-century art, sold the painting to CMA in 1960. A search of his records at the Archives of American Art (now available digitally) revealed that Spark had purchased the painting in 1960 from Francis Moro, who operated a painting conservation studio in New York City. Moro was also an art dealer and, in 1966, opened Moro Galleries, Inc. However, without knowing the circumstances of Moro’s acquisition of the painting, this discovery didn’t do much to close the 100-year gap remaining in the provenance.

But coincidentally, a CMA curator knew Francis Moro’s nephew, who was familiar with a bit of the story of his uncle’s acquisition of the painting. Moro bought the painting from a private collector who had seen the painting displayed in the window of a New York City antique store, where he purchased it. The identities of both this collector and of the antique store appear to be lost to history. And of course, we still don’t know when these transactions took place: Was the painting in an antique store in the 1950s, or in the 1890s? Sadly, we just don’t – and possibly can’t – know. And so, I entered this new information into the provenance, albeit without specific names and dates.

Armed with these newly discovered details that, while interesting, provided little concrete provenance, I then tried to close the gap from 1854 onward.

In 1855, the James family moved to Europe, returning four years later to reside mainly in Newport, Rhode Island, where they lived until they settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1865. Also in 1865, Henry James, Sr. sold their 14th Street house in Manhattan to William Brenton Greene, who had rented it while the James family was in Europe and Newport. Thus, one theory emerged as the most likely path taken by the painting:

Alfred Habegger, a noted Henry James scholar, told me it was quite possible the painting was simply left on the walls of the 14th Street house when the family went to Europe before it was eventually sold, along with the house, to Greene. According to contemporary New York City directories, Mary Harkin – who is listed in the city directory as a seamstress – lived in the house after Greene moved out. Habegger recalled that Greene had a connection to the fashion industry and, therefore, may have “gifted” the Cole to Harkin, whom he may have known.

Alternatively, perhaps the painting was passed down through Greene’s family after he moved out of the house. In hopes of verifying this possibility, I combed through the wills of three generations of Greene family members, only to come up empty. Most of the wills I consulted made no mention of artwork, and the one that did, did not refer to any paintings by name.

Because the painting ultimately made its way to a New York City antique shop, and because it was also in New York City in the mid-1850s, it is quite possible that the painting never left the city, remaining in the James home, passing down through the Greene family – or perhaps the Harkin family – or following some other path into the twentieth century. We do know that as of 1913, the painting was “long ago lost” to the James family’s “sight,” and so, it is certainly conceivable that when the family moved to Europe in 1855, that was also the last time they saw their Cole.

After my research, the painting’s provenance is as follows:

1838-1839? Possibly Mr. Hunt, Boston

By 1839 Jonathan Mason, Boston

By 1848 – before 1854 Edward James, New York, NY, probably to Henry James, Sr.)

By 1854-? Henry James, Sr. [1811-1882], New York, NY

? (Antique store, New York, NY, sold to a private collector)

? Private collector, New York, NY, sold to Francis Moro

Until 1960 Francis Moro, New York, NY, sold to Victor Spark

By 1961 (Victor Spark, New York, NY, sold to CMA)

1961- The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

Thus, I was able to correct an inaccuracy and update the provenance of View of Florence with some additional, if vague, information. I included none of the Greene or Harkin material in the painting’s “official” provenance because, without documentation, it is, at this point, only conjecture. And so, the gap remains unclosed, my mission unfulfilled – at least until new details about this fascinating history are uncovered.

For more information about this provenance, see http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1961.39.

About Victoria Sears Goldman

Partner and co-founder Victoria Sears Goldman, Ph.D., has more than 10 years of experience conducting provenance, art historical, and art market research. Most recently, she worked as a senior director and the lead practitioner in the art risk practice at a leading global risk advisory and investigations firm. Prior to that, Victoria was the provenance researcher at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where she investigated the ownership histories of approximately 150 paintings and sculptures in the museum’s permanent collection. Read more about Victoria’s career here.